Recently, I decided to back my practical prompt engineering skills with some structure and theory and took the AWS Foundations of Prompt Engineering course.

While it allowed me to connect some dots and learn the names of the approaches I was already using, some of the “foundations” seem to be built on quicksand. The chapters with good and bad examples of prompt engineering specifically. Let’s dissect, shall we? Rant incoming.

Exhibit A: How Not to Sum Numbers

In the chapter on the basics of prompt engineering, AWS’ course boldly offers a lesson in clarity, recommending: “Be clear and concise.” Well, my tech writer’s heart couldn’t be happier with the statement. But here’s what is suggested as the “bad” and “good” prompts:

Bad Prompt:

"Compute the sum total of the subsequent sequence of numerals: 4, 8, 12, 16."

Good Prompt:

"What is the sum of these numbers: 4, 8, 12, 16?"

Now hold your horses. In my book, the supposed “bad prompt” is a little formal, unnecessarily flowery, yes. But is it really “bad”? No, it’s perfectly understandable, just awkwardly phrased. Will burn up more tokens and get you a wordy result but a result still. A cat walking over a keyboard – that’s a bad prompt. No clear question is a bad prompt. For this case, “4, 8, 12, 16?” would be a bad prompt.

But we’re interested in good prompts here. So if clarity and brevity truly mattered, wouldn’t a better prompt actually look like:

"Sum total 4 8 12 16?"

Hell, make it even more concise and efficient:

"4 8 12 16 sum?"

Shorter, clearer, and cheaper on token space (~5 tokens as per ChatGPT’s estimation). But no, the course insists on full-sentence politeness. Adorable.

Exhibit B: Basic Arithmetic Sabotage (Or, how to artificially engineer failure)

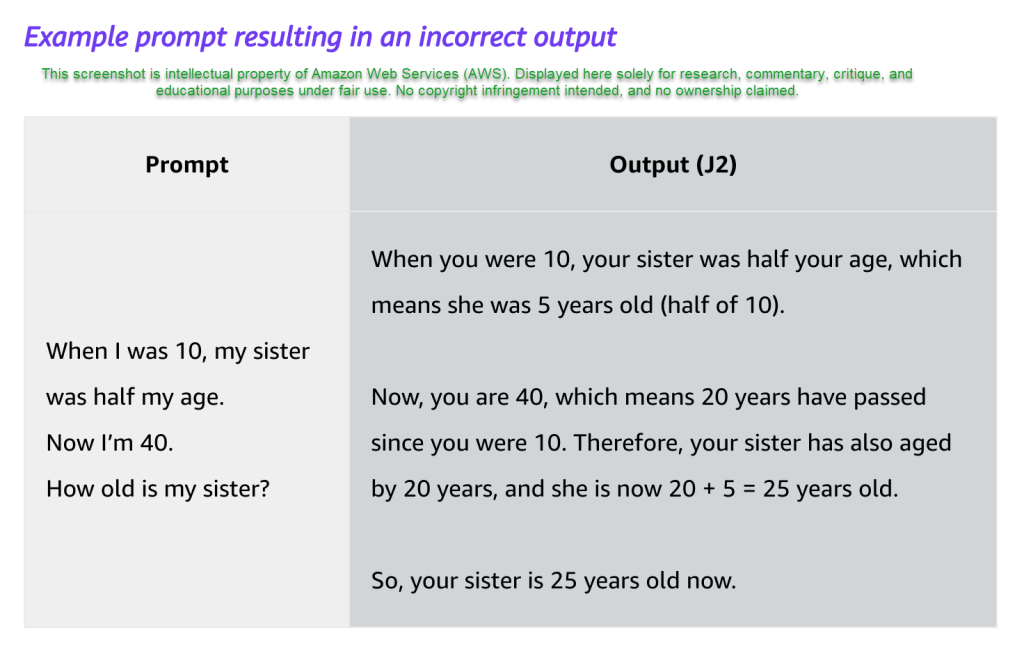

This is where it gets worse. The “advanced” chapter on self-consistency and Chain-of-Thought prompting. Here, AWS tries to demonstrate the limitations of basic prompts, crafting a scenario to highlight the advantage of Chain-of-Thought prompting. Here’s their jaw-dropping example:

Prompt:

"When I was 10, my sister was half my age. Now I’m 40. How old is my sister?"

AWS’ provided model response (Jurassic-2):

“When you were 10, your sister was half your age, which means she was 5 years old. Now, you are 40, which means 20 years have passed since you were 10. Therefore, your sister has also aged by 20 years, and she is now 20 + 5 = 25 years old.”

Did you catch that, dear reader? AWS engineered the model response to contain a blatant math error claiming “20 years” have passed when it’s clearly 30 years. A basic arithmetic mistake, purely contrived to prove the limitations of simple prompting.

So not only this AWS course is teaching you subpar prompt engineering, but the examples are doctored to “prove” a point. Charming.

The Takeaway (or the “don’t do this at home”)

While the course is really awesome at providing a high-level overview of how LLMs are created and what makes the LLMs tick, it would be a consistently great course for beginners if it stuck to its high-level overview guns.

With the “practical” recommendations regarding prompt engineering, it’s foundational malpractice in prompt engineering education. If your “bad” examples aren’t genuinely bad, and your advanced examples rely on doctored outputs, what exactly are you teaching?

If the intention was to educate beginners, now we’ve got a bunch of course alumni who are thoroughly confused regarding the real-world best practices of prompt engineering. But if the intent was clarity, concise communication, and useful guidance for actual prompt engineers? I’ve got some bad news for you.

My humble advice: for the next training course, maybe ask an actual prompt engineer or a technical writer – someone who writes clear, token-efficient instructions/prompts daily – if your examples make any sense.

Until then, I’ll keep calling out the fine art of prompt sabotage.

Stay sharp, keep your prompts lean, and always question “good” advice.

Leave a comment